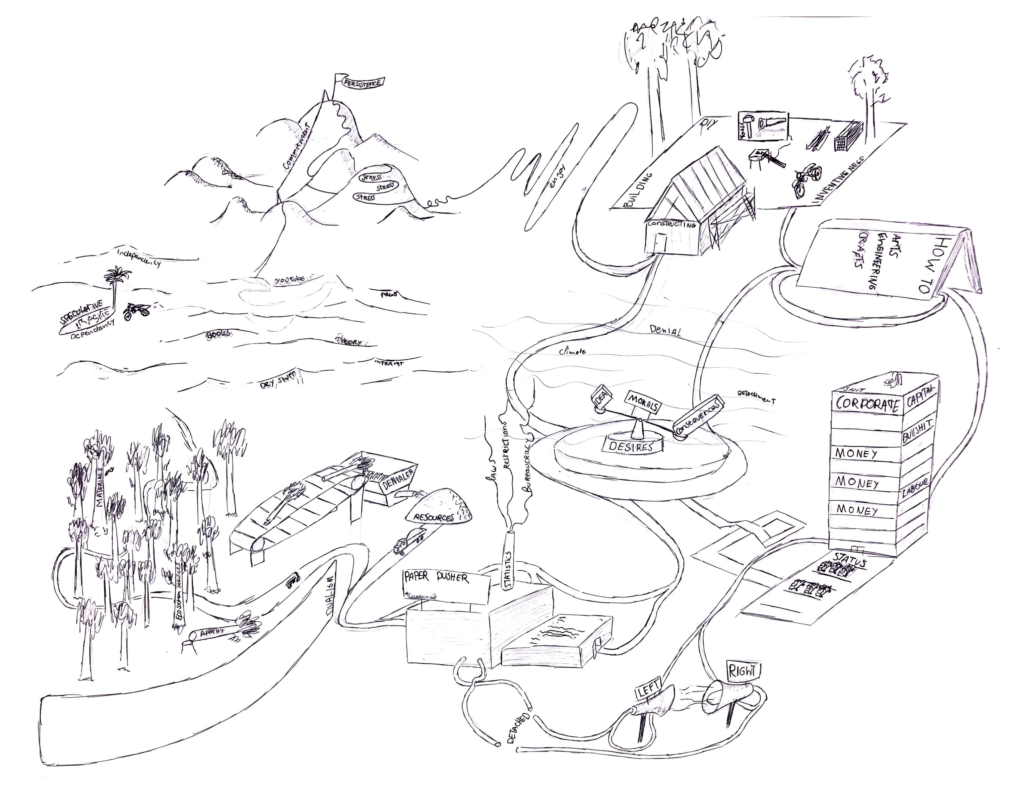

Wicked problems

These problems we are dealing with, so-called wicked problems or hyper objects such as climate change, stay kind of vague and in the air. We know it is happening, however, we do not necessarily know how our own lifestyle is contributing to it. Collectively, we are the problem, but our individual life choices are just a thimble in the ocean. The scale of our society has become so big and ungraspable that we can’t even imagine that the most mundane things such as drinking coffee in the morning are directly contributing to the fact that climate change is happening. These processes, acts, lifestyles and consequences have become so intertwined and entangled with each other that we have become unable to digest them anymore and comprehend how they are related to each other and ourselves. It is not the individual act that creates a problem, it is the collective realization of our desires when it becomes problematic. But if so, how do we justify our material desires?

According to Buckminster Fuller; ‘Society operates on the theory that specialization is the key to success, not realizing that specialization precludes comprehensive thinking’. Outside of our specialized subjects, the work we perform daily in order to survive within this system, we are living in some sort of ‘‘groovy’’ dimension. One where we observe the things we do and use daily in a romantic way, only looking at them in terms of appearance and promises rather than their relationships within these bigger systems and the part that they (and thus we) play in it. We judge the new iPhone against the older model, instead of looking at the implications of another product that makes the older version obsolete.

As a result of the scale and entanglement of todays world, there is a collective feeling amongst us that the world outside of our own individual world is unchangeable. Because of this we have turned to ourselves and hope that our individual choices influence the world outside of our individual perception. Of course this has been fully encapsulated by the marketing machine that is omnipresent in our society, in the words of Hal Foster; ‘Desire is not only registered in products today, it is specified there: a self interpellation of ‘’hey, that’s me’’ greets the consumer in catalogues and on-line’.

We buy our own identities. If you want to change the world, all you have to do is buy yourself a sustainable lifestyle; biological meat, soap bars, ecological toilet paper, and of course an electric car. You can buy yourself a clean consciousness. But we are only looking at what the electric car itself is and compare it to the previous product, rather than what the implications of the product could be. ‘Everything we own contains traces of the vast, complex problem that is atmospheric pollution … and may help to problematize the part we all play in it.’* In order to become aware of the part that we all play in this, we should first of all become aware of our intimate relationship with it.

*Noortje Marres, Labour of Interpretation